In conversation with Yves Veulliet, Associate Worldwide for bdi, on disability confidence and looking people in the eye

Yves, along with personal experience of living with a disability you have a senior mandate to increase the inclusion and employment of people with disabilities at work, tell me a little about your current role…

In 2014 I was appointed to the role of Global Diversity and Inclusion Manager at IBM with a clear mission to facilitate greater inclusion of employees with different abilities. My role involves collaborating with key stakeholders across the world and across the business to promote disability in the workplace, and identifying and removing factors that inhibit inclusion.

In my experience awareness is not enough, people with disabilities experience many types of obstacle; physical, technological, psychological and cultural. My role is to work out how we can put in place the right solutions and processes to ensure that people with disabilities can be as productive and successful as anyone else. On the accessibility front this means: ensuring that our buildings, websites, recruitment processes and IT systems are all as accessible as possible, and on the accommodation front: making sure that our employees with disabilities get the accommodations and workplace adjustments they need, and that the costs related to the provision of these adjustments are charged to a central budget i.e. not to employee’s department.

Clearly a proportion of your work is focused at Head Office level, but tell me a bit more about how you support local implementation and adaptation of IBMs global inclusion policy and practice…

IBM works in 170 countries, so my role is to connect the dots across the organisation and to help individual countries and regions with their specific and varied challenges. Like many global organisations, one of the biggest challenges is around recruitment of people with disabilities, as IBM primarily recruits university graduates and those who have accessed higher education.

In many countries in the world, people with disabilities have limited or restricted access to education at all levels, including higher education, so our ability to recruit people living with a disability in these countries is, by consequence, reduced.

We therefore do a considerable amount of work with local partners and charities in these countries to foster and support disabled talent and build a pipeline of potential disabled applicants. In major markets we work with universities in academy partnerships, whereby we provide technical support to improve the accessibility of the university’s IT infrastructure in return for their commitment to support disabled students, who might then apply for internships or employment with IBM.

Additionally, as part of our CSR programmes in developing countries and growth markets we have a long term strategy to engage with local NGOs to facilitate greater access to education for disabled children from primary school through to higher education. This work takes time and effort, but only an innovative and committed approach over the long term will really deliver greater inclusion, and this is what I promote when sharing IBM’s approach to inclusion with global partners and organisations.

For a global business, what is the most challenging part of an organisation becoming disability confident?…

The main issue is rarely about improving physical or virtual accessibility or making adjustments and accommodations. Whilst these elements are not easy, with strong senior leadership and appropriate resources allocated to these tasks you can work through the operational and policy changes that are necessary.

The more difficult part is consistently changing attitudes and mindset, as there is a cultural dimension to this. My own experience since joining IBM in 1992 has been very positive. Despite being a wheelchair user at the time I was recruited, IBM saw beyond my disability to the skills and expertise I could offer to the company in a core business role. Ultimately it is the ability of front-line managers to become disability confident that dictates whether or not a company is disability confident and can recruit, employ and do business with people with disabilities.

Having come through the company from a business role to my current position focused on diversity and inclusion, I understand the pressures and reality of being in a customer-facing role with targets to hit. Understanding and communicating the rationale for disability confidence in this context is vital.

That is why one of our key programmes is the delivery of training for first line managers, usually and ideally as part of a face-to-face 2hr workshop. These managers often have limited exposure and access to people with disabilities, they have conscious and sub-conscious preconceptions about what employing people with disabilities would mean for them. They need to be convinced that it won’t cost them money, or impact on their team’s productivity or targets. As an individual who has worked in a business role for IBM, and has personal experience of living and working with a disability, I find I can talk their language and this training is very impactful and effective and is being delivered all over the world from Israel to Poland to Austria.

What are the best and worst examples of disability confidence that you have seen recently and why?…

In what a sad example of the cultural dimension to disability, a business partner living in the Asia told me no later than last week: “We do not hire people with disabilities for client facing positions: it is not appropriate for them to meet with our clients.” The incorrect assumption behind this statement is that we don’t want to damage the image of our firm by “showing” we have employees with disability. This proves that companies must continue to work to change understanding of disability.

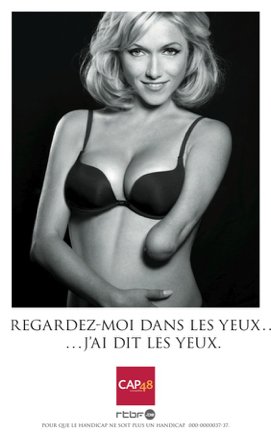

A great example is something I saw in the media recently. In the world of fashion, appearance is key, right? Look at this model… The legend reads “Look at me in the eyes… I said in the eyes”

You touched on the cultural dimension to disability in your examples above and I know that globally there are some strange myths and preconceptions about people with disabilities. What is strangest thing anyone has ever said to you about disability?…

In some African countries, because of a literal interpretation of theological perspectives, people view disability as ‘virtuous suffering’. Disability has been identified as suffering that must be endured in order to purify the righteous, a teaching that encourages passive acceptance of social barriers for the sake of obedience to God. Clearly this makes increasing inclusion of people with disabilities in the workplace very challenging in certain countries.

How does IBM position disability within the organisation?…

When I took on my role within diversity and inclusion, one of the comments I heard most was the misconception that ‘people with disabilities need workplace adjustments’ and the implication that these adjustments cost money.

My stance and IBM’s policy is that it will provide all the necessary accommodations and adjustments to enable people with disabilities to be as productive as anyone else. Beyond that, it is the responsibility of every individual, disabled or not, to make the most of all that IBM offers. People with disabilities do not have specific performance programmes or career development schemes, once the appropriate workplace adjustments are in place, everyone is equal at IBM and must succeed on their own merit.

How have you managed that common objection that ‘workplace adjustments cost money,’ as I know this is something that bdi Founders and Members have cited as a common query?…

We have taken the costs away from managers’ budgets and all appropriate adjustments come from a Global Welfare Budget which we can track at a country level. This is a very important message as it removes a major obstacle in people’s minds and in practice. Costs for workplace adjustments are bourn centrally as it removes the myth of prohibitive costs to adapt for disability. Of course, not all adjustments have a cost, accommodations like flexible work hours have no cost, so we simply have to keep educating about the importance of making adjustments to ensure that every employee, disabled or not can be productive.

It sounds like you have strong support at a senior level to deliver greater inclusion across the business, what role do your senior leaders and executives play in endorsing and enhancing your work?…

At IBM we have a Global Disability Council, made up of SVPs and VPs from across the organisation and representing different business units. We ask them to leverage their visibility and influence to promote disability in the workplace, but we also ask for their active involvement in delivering key initiatives.

One key part of their active involvement is that for a 6 month period they regularly mentor a disabled employee who has been identified by our business development team as a future leader. Mentorship is a vital development opportunity for all employees, but this practical and simple scheme provides strong mutual benefits to the leader and the employee. The leader can understand first-hand what barriers to accessibility and inclusion still exist in the company, and the mentee can benefit from the network, experience and insights of the senior leader as it customary of any mentorship programme. It is very important for senior leaders to develop their own personal confidence with people with disabilities so that their commitment extends beyond mere communication.

Personal exposure to people with disabilities is a crucial part of disability confidence. With the media spotlight now on the Paralympics in Rio, do you think that this helps people understand disability?…

Of course increasing the visibility of people with disabilities is good, including those whose disabilities are less visible to the naked eye. However, my personal view is that whilst it increases awareness of disability and the potential of people, with disabilities it does not really assist with increasing inclusion of people with disabilities in the workplace.

Being a Paralympic athlete is an amazing achievement. The personal stories that are being shared in the media demonstrate the extraordinary journeys and obstacles that many people with disabilities have faced as they, their family and peers learn to cope and to thrive whilst living with a disability. Indeed this is the subject of a book I wrote called ‘Turning Point – The fall and rise’ (at on-line retailers such as Amazon) about my own experience coming to terms with a disability, as most disabilities are acquired post birth.

That said, most business organisations do not need swimmers, rowers or basketball players, disabled or not. The language of business is about ROI, productivity, business skills and expertise, and the Paralympics does not use this language. Increasing awareness of disability generally is good, but this is not enough to make a real difference to disability and inclusion in the workplace.

How right you are, and this makes the programmes you are delivering so important to IBM, to global business, and to people with disabilities seeking a career in the corporate world. I hope that other organisations and leaders can learn from what we have discussed today as they seek to make changes within their own organisations to become more disability confident.

Thanks for your time and thoughts Yves and I look forward to hearing how you work at IBM progresses over the years and months ahead.

For more information about Yves

- LinkedIn profile

- Turning Point – The Rise and Fall. Available on Amazon UK and Amazon.com (5 stars reviews!)

or to read more about IBM, please follow the links below - IBM accessible technologies and best practices

- IBM Diversity brochure

Leave A Comment